Lecanemab, a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, received an expedited approval from the Food and Drug Administration on Friday. This is the second treatment from Biogen and its Japanese partner Eisai to receive an early green light in less than two years.

After clinical trial results that were published in November showed that lecanemab slows cognitive decline somewhat in people with mild Alzheimer’s disease, the FDA approved the treatment. However, the treatment also carries risks of swelling and bleeding the brain.

Lecanemab was developed by Eisai, which is selling the treatment under the name Leqembi for $26,500 per year in the United States.

If a drug is expected to help patients with serious conditions more than what is currently available, the FDA can accelerate its approval in order to quickly bring it to market. In July, Eisai and Biogen made a request for an expedited approval.

In a statement, FDA neuroscience division director Dr. Billy Dunn said, “Alzheimer’s disease immeasurably incapacitates the lives of those who suffer from it and has devastating effects on their loved ones.” “This treatment option is the latest therapy to target and affect the underlying disease process of Alzheimer’s, instead of only treating the symptoms of the disease.”

Alzheimer’s affects more than 6.5 million people in the United States. Memory, thinking abilities, and eventually the capacity to carry out simple tasks are all destroyed by the incurable disease.

After Congress issued a scathing report last week regarding the FDA’s handling of the contentious approval of Aduhelm, a second Alzheimer’s drug developed by Biogen and Eisai, the decision on lecanameb follows. The report says that that treatment’s approval in 2021 was “rife with irregularities” because experts said it didn’t show a clear clinical benefit.

“FDA must take swift action to ensure that its processes for reviewing future Alzheimer’s disease treatments do not lead to the same doubts about the integrity of FDA’s review.” the congressional report stated.

Slows disease mildly

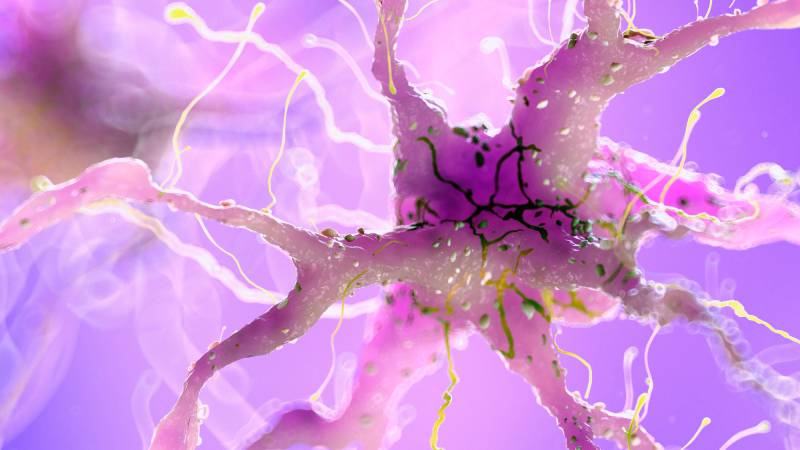

Lecanemab is a monoclonal antibody that targets amyloid, a protein that accumulates in Alzheimer’s patients’ brains. Every two weeks, the patient receives 10 milligrams of the antibody per kilogram of body weight via intravenous injection.

According to a statement issued by the agency, the reduction in amyloid plaque observed in clinical trial participants who received lecanemab was the basis for the FDA’s approval of the drug. Amyloid plaque did not decrease in those in the placebo group who did not receive the treatment.

According to the findings of the clinical trial, which were published in the New England Journal of Medicine, participants who received lecanemab had a 27% slower rate of cognitive decline over the course of 18 months than those who did not receive the treatment. Biogen and Eisai provided funding for the study.

The clinical dementia rating, an 18-point scale with a higher score indicating greater impairment, was used to measure cognitive decline. It measures memory, judgment, and problem-solving abilities in the brain.

The average progression of Alzheimer’s disease was 1.21 points in the group that received lecanemab, compared to 1.66 points in the group that did not receive the treatment, a 0.45 point difference.

The trial involved nearly 1,800 individuals with early Alzheimer’s disease, half of whom received lecanemab and the other half did not.

Concerns about safety

Despite the fact that lecanemab may somewhat slow cognitive decline, the treatment carries risks as well.

Brain swelling occurred in nearly 13% of those who received lecanemab, compared to about 2% of those who did not. However, the majority of these cases did not cause symptoms, were mild to moderate in severity, and typically resolved within four months.

Lecanemab treatment resulted in more severe brain swelling in about 3% of patients, causing headaches, visual disturbances, and confusion.

Brain bleeding occurred in approximately 17% of those who received lecanemab, compared to 9% of those who did not. Dizziness was the most common symptom that came with the bleeding.

In the clinical trial, serious adverse events occurred in 14% of those who received lecanemab, compared to 11% of those who did not.

Lecanemab’s efficacy and safety in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease, according to the study’s authors, need to be tested in larger clinical trials for a longer period of time.

Lecanemab’s prescribing instructions, according to the FDA, will include a warning about the possibility of swelling and bleeding, also known as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities.

A research letter that was recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests that lecanemab may also have been a factor in the death of a Chicago-area participant in a clinical trial.

Four days after their third lecanemab infusion, the 65-year-old suffered a stroke and was hospitalized. After the patient’s stroke, a CT scan revealed extensive brain bleeding. 81 days prior to the stroke, no bleeding was detected on an MRI.

Additionally, the patient had been given t-PA, a drug that is used to break up blood clots that cause strokes. However, the doctors who wrote the research letter claim that this medication on its own would not typically result in extensive brain bleeding.

In a response letter, researchers who were part of the lecanemab clinical trial argued that the blood clot medication appeared to be the immediate cause of the patient’s death, with the first symptoms appearing 8 minutes after they received an infusion of the blood clot buster.

- IPL Icon MS Dhoni Makes Unbelievable Record Against SRH - April 26, 2025

- Cougars Coach Kelvin Sampson Chases 800th Career Victory in NCAA Finals - April 8, 2025

- How to Check IIT GATE 2025 Results Online? Complete Guide - March 19, 2025